Explaining Microservices Properly

Microservices are actually pretty cool if you know how design them correctly!

Published 09/11/2025

Table of Contents

Why I'm Writing This

It was really hard to research microservices for some reason. Either explanations online were too simple, or too complex. In my research, I found the holy grail of talks, one which clarified everything for me.

This article is primarily based on "Don't build a distributed monolith" by Jonathan J. Tower , which explained everything, perfectly. If you want to research this further, please watch this video instead.

The Monolith Architecture

Monoliths are a basic architecture where the entire backend is done in one codebase , backed by a single database.

Having the entire backend in one codebase has its pros and cons. The architecture is generally easier to grasp, and most developers can apply whatever software engineering principles to the microservice architecture and make a pretty good project.

Scaling a monolith project is relatively easy. You can simply scale up the memory, cpu, storage, etc. for both the database and servers you are hosting the program on. But, if one problem occurs in a single component, then the entire application crashes.

A solution is to simply load-balance the servers, but you still have to ask yourself "is what I’m building really stable?" Figure 2 demonstrates an example of a load balanced monolith.

However, when working on enterprise-grade software where you may have multiple, large development teams, monoliths become a nightmare to work on and manage, especially with git.

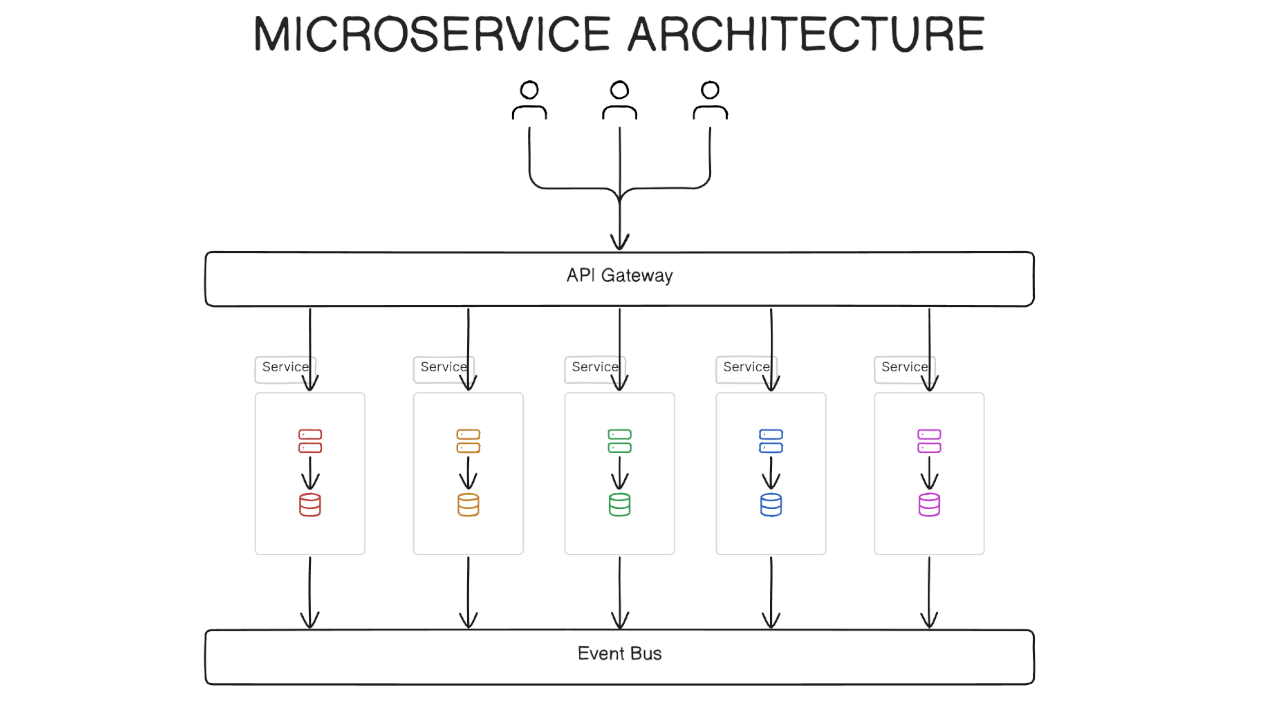

Microservice Architecture

Overview

Microservices are a much more complicated way of architecting software, but provide some notable upsides. Instead of thinking about the one project, you instead think about each individual component/service of the application and deploy them as separate, independent programs. These services communicate with each other via an event bus, and store everything in their own database.

As stated before, each service will maintain its own state/database. This is what makes them independent - when services maintain their own state, they are almost completely decoupled from every other part of the application making them highly available to issues in other services. If one service goes down, everything else can still run on its own.

For example, if you have just one database, it is inevitable that multiple parts of the codebase will reference one SQL table. If the database administrator decides to add a column, modify, or drop one, then every line of code that references that column or table will have to be changed. Having an independent database per service makes it so the database admin can add a column to a service, without affecting everything else.

The Event Bus

The internal state is updated via the event bus. Let's say we have a

UserService

, and the user just decided to create a new account. Once the

UserService

creates the user and stores it in its own database, it will invoke an event like

AddUser(someUsername, age, emailAddress, ...)

. Then, other services can subscribe to those events and update their own database according to the parameters. This means that unlike monoliths, microservices are

eventually consistent

.

The parameters for the event are effectively the contract for that event. We can say that an event must provide all specified parameters to fulfil the event's contract.

The event bus can handle some of the problems that you're already thinking of, like "what happens if a subscriber crashes, and isn’t able to apply the events during its downtime?". Event bus implementations like Apache Kafka store any events during a serivce’s downtime, and apply them once it knows it's back online.

For example, lets say in a traditional monolith application, the database fails for some reason, as illustrated in figure 4.

This could bring down your whole service, or even your monolith! Its pretty hard for a database to just completely shut off, but this is an example. It could really be as simple as an unhandled exception or SEGFAULT.

The point is, shit happens . The question is, how do we minify the destruction caused by unexpected issues? An event bus!

Obviously, core parts of your application won't work anymore. But, at least some of it is , and you'll have more time to diagnosue and solve the issue and bring the service back up to date in the event of a crash.

Note On Performance

Since services are deployed separately, this means microservices have worse throughput when compared to monoliths. The actual performance of the services are just fine - it's just that sending multiple network requests, managing the event bus, etc., do increase the amount of time it takes to manage requests.

Distributed Monoliths

When you allow services to communicate directly with each other, you end up with a distributed monolith, where developers attempt to apply some ideas of the microservice architecture into a monolith application.

Figure 6 shows how interconnecting services together, and avoiding the event bus effectively destroys the point of using microservices in the first place.

In this case, each service could be directly connecting to each other via HTTP endpoints and each service's hostname, instead of sending events as expected. We have effectively gone back to the issue shown in figure 4, where we now need to implement our own outage handling system in each service.

This can be caused by the simple desire to apply "DRY" (don't repeat yourself) principals to your architecture. Instead of making small, independent components that communicate via a decentralised event bus, services are connected directly to each other in an attempt to not repeat yourself.

Its important to understand that microservices fundamentally require repeated code in order to make them highly available. If services use the same database, then if one goes down, the rest do as well. And now all that's left is a distributed monolith, and a whole lot of pain.

Microservices, and Enterprise Software

There is a lot of talk about multiple teams, eventual consistency, and all this complicated stuff that becomes hard to understand why this is even worth considering. With huge enterprise software, there are so many moving parts that it becomes hard to delegate tasks and actually deploy and administer all this software.

By splitting your team into different services, large businesses can rapidly add changes and deploy them without having to re-deploy the entire program like in a classic monolith application.

Avoid Chatty Services

Services should not be chatty - try not to overuse events. Services are advised to be developed in separate teams. You might have a

BookingService

,

AdminService

,

MaintenanceService

, in your hotel application. You would have a team working on each of these services independently, and become experts in that specific service and domain.

When a new requirement comes in, that one small team working on that microservice can update, and deploy it without the other teams needing to worry about it.

Implement Solid CI/CD Pipelines

With good CI/CD pipelines, the deployment process becomes even easier. When everything is decoupled such that breaking changes to different services are less likely, why not just allow developers to automatically deploy software as they please?

CI/CD is applied in version control software allowing actions to be executed when new code is published. With GitHub, an action could be created that states "when new commits are made on the

main

branch, compile and deploy it", with your own build and deployment scripts.

Scaling Microservices

The most interesting feature of microservices is the ability to scale components independently. Because everything is deployed separately, this gives administrators the ability to scale their service vertically up and down as usage grows and shrinks.

Consider Event Contracts Carefully

Event contracts need to be considered carefully. To reiterate, a contract would be the arguments within an action. When a new user is created, an event could be fired with the new username, id, email, etc.

All services are dependent/coupled to the event bus. It is possible that the event bus can change at any point, so development teams need to set rules as to when event contracts are changed.

A good starting point is to apply FreeBSD's Binary Copmatability guidelines to your team. It mentions the following:

"Maintaining a stable ABI is important. Users hate having to recompile things that used to work. A lot of downstream users keep systems for about 10 years and want to be able to keep running their stack on top of FreeBSD without worrying that an upgrade will break things."

An ABI (Application Binary Interface) can be thought of as an event contract in this context. To avoid any compatibility problems in the future, developers must abide by the following rules consistently :

- Don’t add new required fields - only add optional ones

- When field is added, receiver ignores it unless programmed

- If consumer of event sees missing value, use a default one

- If 1 - 3 cannot be satisfied, create a new event

Before You Consider Implementing Microservices

Microservices sound really awesome, and sounds like it would probably fit your use case pretty darn well.

You should ask yourself - am I really developing "enterprise grade" software? You should also ask yourself - is my team going to regret maintaining 5 separate codebases?

Implementing microservices correctly can provide you so many benefits. But in the process, it is not only going to take much longer to get started with, but its also going to be damned expensive.

Maybe unless all of your microservices are just Go+Sqlite instances, deploying several codebases and APIs on AWS should NOT be your first or second approach to solving your problem.

Keep it simple. Start with a monolith. Don't do this to yourself, until your business reaches a point where it can employ enough people to maintain everything, and are willing pay for an eye-watering AWS bill.